This post may contain Mildly Adult content.

This page is a permanent link to the reply below and its nested replies. See all post replies »

CopperCicada · M

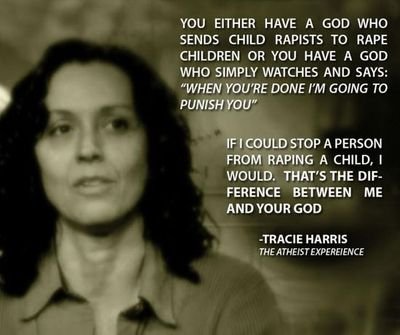

The problem of evil is something that any theist has to face. In formal theology it’s called theodicy. There’s usually two angles to theodicy. To try to understand how evil can exist in a world created by a good God, and to create a vision of God that is is consistent with the reality that the world is fucking awful. There are a bunch of classic Christian theodicies by Augustine, Iraneus, Origin, and modern theologians.

I agree with some modern theologians in that theodicies normalize and forgive evil in the world. They normalize violence, inhumanity, abuse, war, horror. This darkness ends up becoming part of the system: God has a plan, that is why a child is raped. A child is raped because of our sin, our corrupted nature. A world with horrors like a child raped is necessary for us to develop spiritually and know God. All this legitimizes these horrors. Such theology becomes the potential basis for evil.

I agree with some modern theologians in that theodicies normalize and forgive evil in the world. They normalize violence, inhumanity, abuse, war, horror. This darkness ends up becoming part of the system: God has a plan, that is why a child is raped. A child is raped because of our sin, our corrupted nature. A world with horrors like a child raped is necessary for us to develop spiritually and know God. All this legitimizes these horrors. Such theology becomes the potential basis for evil.

@CopperCicada

It is indeed one of the biggest problems for Christians and frankly i don't think i've ever heard any convincing apologetic for it.

Free will, ineffable plan, sins of the father.

These things all fall flat if one considers their god to be omnipotent and benevolent.

It is indeed one of the biggest problems for Christians and frankly i don't think i've ever heard any convincing apologetic for it.

Free will, ineffable plan, sins of the father.

These things all fall flat if one considers their god to be omnipotent and benevolent.

CopperCicada · M

@Pikachu Well, there are ways around theodicy.

In the Jewish tradition after the holocaust, theodicy became a problem. Jewish philosophers of the 20th century went as far as saying theodicy was evil, blasphemous, and so on. So there were emergent anti-theodicy theologies.

Most notably the theology of protest. Basically the Jews could not, and can not, forgive God for the holocaust. And so they must protest— to God. The antecedents are in the story of Job where here doesn’t question God’s existence or power, but God’s sense of ethics, morality, justice.

The endpoint to these anti-theodicies is really a humanistic commitment to justice.

There are similar anti-theodicies in Christianity which end up not at a stone cold justification of evil in a world created by an all good God, but again, at a commitment to justice. One Christian anti-theodicy emphasizes meditation on tragedy, suffering, injustice, etc., rather than trying to ask why God allowed them to happen. One ends up with the commitment, again, to justice.

I’d recommend Jung’s The Answer to Job by Carl Jung. Jung identifies a part of God that is evil, and in some sense the Christian mystery is about God’s redemption of evil through sacrificing Christ. In some sense, the Christian mystery being a psychological evolution of God from the Old Testament God. It’s not a theological text obviously, but a very deep addressing of God and evil.

In the Jewish tradition after the holocaust, theodicy became a problem. Jewish philosophers of the 20th century went as far as saying theodicy was evil, blasphemous, and so on. So there were emergent anti-theodicy theologies.

Most notably the theology of protest. Basically the Jews could not, and can not, forgive God for the holocaust. And so they must protest— to God. The antecedents are in the story of Job where here doesn’t question God’s existence or power, but God’s sense of ethics, morality, justice.

The endpoint to these anti-theodicies is really a humanistic commitment to justice.

There are similar anti-theodicies in Christianity which end up not at a stone cold justification of evil in a world created by an all good God, but again, at a commitment to justice. One Christian anti-theodicy emphasizes meditation on tragedy, suffering, injustice, etc., rather than trying to ask why God allowed them to happen. One ends up with the commitment, again, to justice.

I’d recommend Jung’s The Answer to Job by Carl Jung. Jung identifies a part of God that is evil, and in some sense the Christian mystery is about God’s redemption of evil through sacrificing Christ. In some sense, the Christian mystery being a psychological evolution of God from the Old Testament God. It’s not a theological text obviously, but a very deep addressing of God and evil.

@CopperCicada

I kinda wonder why Jews would struggle with this at all.

God's wrath and judgements are many and brutal throughout their scripture.

Isn't the problem evil pretty readily solved (and often explicitly identified by prophets) as "y'all are making god angry with your wicked ways"?

I kinda wonder why Jews would struggle with this at all.

God's wrath and judgements are many and brutal throughout their scripture.

Isn't the problem evil pretty readily solved (and often explicitly identified by prophets) as "y'all are making god angry with your wicked ways"?

CopperCicada · M

@Pikachu Theodicy is a huge part of traditional Jewish theology. I mean, they were the chosen people, God’s favorites, and God put them threw some shit. The Old Testament is full of examples of theodicy.

But the holocaust changed that. How can you believe in a loving God after that? So there is a whole movement of post holocaust Jewish theology. From what I could tell reading about it, all anti-theodicy.

What’s interesting is that the work of some of these holocaust theologians has been extended to child abuse and the same questions it provides. How do you have a God that allows that? You can’t, unless it is through protest.

But the holocaust changed that. How can you believe in a loving God after that? So there is a whole movement of post holocaust Jewish theology. From what I could tell reading about it, all anti-theodicy.

What’s interesting is that the work of some of these holocaust theologians has been extended to child abuse and the same questions it provides. How do you have a God that allows that? You can’t, unless it is through protest.

@CopperCicada

Well obviously i'm no Jewish scholar lol. But i just don't see the issue for them.

Burning the wrong sort of incense is punishable by being burned alive lol

Well obviously i'm no Jewish scholar lol. But i just don't see the issue for them.

Burning the wrong sort of incense is punishable by being burned alive lol

CopperCicada · M

@Pikachu I think the point is that after the holocaust the question of reconciling evil in a world created by a good and just God was off the table. Theodicy was not an option.

The only option was to give up the faith, and many did. Or to be angry and challenge God. And follow that to its endpoint— a commitment to justice here and now.

The only option was to give up the faith, and many did. Or to be angry and challenge God. And follow that to its endpoint— a commitment to justice here and now.