Aquatic Bow

[media=https://youtu.be/4Uln9cwUFOs]

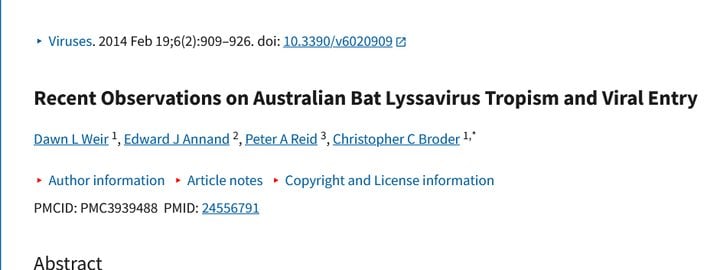

Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV) is a recently emerged rhabdovirus of the genus lyssavirus considered endemic in Australian bat populations that causes a neurological disease in people indistinguishable from clinical rabies. There are two distinct variants of ABLV, one that circulates in frugivorous bats (genus Pteropus) and the other in insectivorous microbats (genus Saccolaimus). Three fatal human cases of ABLV infection have been reported, the most recent in 2013, and each manifested as acute encephalitis but with variable incubation periods. Importantly, two equine cases also arose recently in 2013, the first occurrence of ABLV in a species other than bats or humans. Similar to other rhabdoviruses, ABLV infects host cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis and subsequent pH-dependent fusion facilitated by its single fusogenic envelope glycoprotein (G). Recent studies have revealed that proposed rabies virus (RABV) receptors are not sufficient to permit ABLV entry into host cells and that the unknown receptor is broadly conserved among mammalian species. However, despite clear tropism differences between ABLV and RABV, the two viruses appear to utilize similar endocytic entry pathways. The recent human and horse infections highlight the importance of continued Australian public health awareness of this emerging pathogen.

The discovery of Hendra virus (HeV), a lethal paramyxovirus that emerged in Australia in 1994 [1], indirectly led to the discovery of Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), the first endemic lyssavirus isolated in Australia. In 1996, a retrospective study to identify the natural host of HeV was initiated. Serological evidence pointed to pteropid bats, also known as flying foxes, as the likely host reservoir of HeV [2]; indeed, HeV was subsequently isolated from these bats [3]. Brain tissue samples from two female black flying foxes collected from Ballina, Northern New South Wales (NSW) tested negative for HeV antibodies [4]. One sample, collected in 1996, was from a juvenile female black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) that was found under a tree and unable to fly; the other was a fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sample from a female black flying fox collected the previous year that had been euthanized and necropsied due to its unusually aggressive behavior [4]. Histological analyses of brain tissue from the 1996 bat showed severe nonsuppurative encephalitis. Encephalitis was mild in the 1995 bat brain sections but numerous cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, indicative of lyssavirus infection, were present and immunohistochemical analyses revealed the presence of lyssavirus nucleocapsid antigen throughout the brain of both bats [4]. Blood from the 1996 bat tested negative for anti-RABV neutralizing antibodies and virus could not be isolated by direct culture, but virus was subsequently isolated through intracerebral inoculation of kidney homogenate into weanling mice and further passaging in both mice and mouse neuroblastoma cells. The virus was shown to be neutralized by anti-RABV sera; however, the pattern of monoclonal antibody (mAb) binding of a panel of lyssavirus nucleoprotein (N) antibodies revealed that this lyssavirus was serologically distinct from RABV and other known lyssaviruses [4]. Sequence comparisons of the ABLV N protein and other lyssavirus N proteins showed that ABLV was most closely related to European bat lyssavirus-1 (EBLV1) and RABV with 93% and 92% amino acid identity, respectively [4,5]. Based on these results, as well as the anti-N mAb binding data, ABLV was designated as a new lyssavirus genotype.

The discovery of Hendra virus (HeV), a lethal paramyxovirus that emerged in Australia in 1994 [1], indirectly led to the discovery of Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), the first endemic lyssavirus isolated in Australia. In 1996, a retrospective study to identify the natural host of HeV was initiated. Serological evidence pointed to pteropid bats, also known as flying foxes, as the likely host reservoir of HeV [2]; indeed, HeV was subsequently isolated from these bats [3]. Brain tissue samples from two female black flying foxes collected from Ballina, Northern New South Wales (NSW) tested negative for HeV antibodies [4]. One sample, collected in 1996, was from a juvenile female black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) that was found under a tree and unable to fly; the other was a fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sample from a female black flying fox collected the previous year that had been euthanized and necropsied due to its unusually aggressive behavior [4]. Histological analyses of brain tissue from the 1996 bat showed severe nonsuppurative encephalitis. Encephalitis was mild in the 1995 bat brain sections but numerous cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, indicative of lyssavirus infection, were present and immunohistochemical analyses revealed the presence of lyssavirus nucleocapsid antigen throughout the brain of both bats [4]. Blood from the 1996 bat tested negative for anti-RABV neutralizing antibodies and virus could not be isolated by direct culture, but virus was subsequently isolated through intracerebral inoculation of kidney homogenate into weanling mice and further passaging in both mice and mouse neuroblastoma cells. The virus was shown to be neutralized by anti-RABV sera; however, the pattern of monoclonal antibody (mAb) binding of a panel of lyssavirus nucleoprotein (N) antibodies revealed that this lyssavirus was serologically distinct from RABV and other known lyssaviruses [4]. Sequence comparisons of the ABLV N protein and other lyssavirus N proteins showed that ABLV was most closely related to European bat lyssavirus-1 (EBLV1) and RABV with 93% and 92% amino acid identity, respectively [4,5]. Based on these results, as well as the anti-N mAb binding data, ABLV was designated as a new lyssavirus genotype.

...