Book to share - October 2024

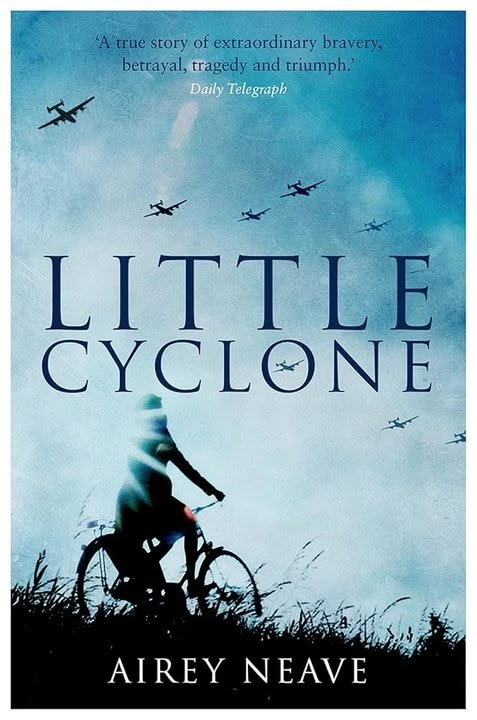

Little Cyclone: The Girl Who Started the Comet Line by Airey Neave (1954)

The exhilarating true story of the greatest escape route of the Second World War. On a hot afternoon in August 1941, a 24-year-old Belgian woman walks into the British consulate in Bilbao, neutral Spain, and demands to see the consul. She presents him with a British soldier she has smuggled all the way from Brussels, through Occupied France and over the Pyrenees.

It is a journey she will make countless times thereafter, at unthinkable danger to her own life. Her name is Andrée de Jongh, though she will come to be known as the 'Little Cyclone' in tribute to her extraordinary courage and tenacity. And she is an inspiration. From nursing wounded Allied servicemen, de Jongh will go on to establish the most famous escape line of the Second World War, saving the lives of more than 800 airmen and soldiers stranded behind enemy lines.

The risks, however, will be enormous. The cost, unspeakably tragic. Her story is shot through with the constant terror of discovery and interception - of late-night knocks at the door, of disastrous moonlit river crossings, Gestapo infiltrators, firing squads and concentration camps. It is also a classic true story of fear overcome by giddying bravery. Estimates of the number of times that de Jongh herself successfully escorted downed airmen across the border into Spain in 1941 and 1942 vary from 16 to 24 round trips. The number of persons, mostly airmen, she escorted successfully is about 118.

Originally published shortly after the war, Little Cyclone is thus a mesmerising tale of the best of humanity in the most unforgiving circumstances: a remarkable and inspiring account to rival the most dramatic of thrillers. Royalties from the sale of this book will go to the Airey Neave Trust. The objective of the trust is to support and promote research that contributes in a practical way to the struggle against international terrorist activity.

De Jongh rejected efforts by the British and the Belgian government in exile to control or direct the Comet Line. British agent Donald Darling (code name "Sunday") who worked for MI6 and MI9 gave her the code name of "Postman", and that's now the title of a second book on de Jongh written by Michael Kenneth Smith (2018). In 1943 she finally got betrayed and arrested herself, and then interrogated nineteen times by the Abwehr (German military intelligence) and twice by the Gestapo. Although she admitted being the leader of the Comet Line to protect her father who was under suspicion, the Germans did not believe that this slight, young woman was more than a minor helper.

Underestimation of de Jongh's importance in the Comet Line probably saved her from execution. Later, while she was a prisoner in Ravensbrück, the Gestapo realized who she was and searched for her, but she eluded them by hiding her identity. After her concentration camp experiences, de Jongh resurfaced in summer 1945 in the middle of the night at Donald Darling's Paris Awards Office. She still wore the pink and white striped dress that was the camp uniform. She was thin and suffering from health problems that lasted for the rest of her life.

Andrée de Jongh was awarded after the war the George Medal (the supreme British civilian decoration), the US Medal of Freedom with golden palms, the Presidential Medal of Freedom (the supreme US civilian decoration), the Belgian Croix de Guerre with palms, and made Chevalier of the French Legion d'honneur and of the Belgian order of King Leopold. She continued her life with a sense of purpose, married fellow resistance member Florentino Iñiguez and moved to the Congo, where she dedicated herself to humanitarian work by working amongst people affected by leprosy. She also worked in Cameroon, Ethiopia and Senegal before ill health brought her back to Belgium. In 1985 she was made a Countess in the Belgian nobility by King Baudouin.

Airey Neave served as an intelligence agent for MI9 in World War Two. This was a section of the British Directorate of Military Intelligence, part of the War Office. During the Second World War it was responsible for obtaining information from enemy prisoners of war. The author of several highly acclaimed books on the Second World War, Neave died in 1979 in an IRA a car-bomb attack at the House of Commons. Margaret Thatcher was due to broadcast to the nation that evening, but cancelled her plans due to her grief at Neave's death.

The exhilarating true story of the greatest escape route of the Second World War. On a hot afternoon in August 1941, a 24-year-old Belgian woman walks into the British consulate in Bilbao, neutral Spain, and demands to see the consul. She presents him with a British soldier she has smuggled all the way from Brussels, through Occupied France and over the Pyrenees.

It is a journey she will make countless times thereafter, at unthinkable danger to her own life. Her name is Andrée de Jongh, though she will come to be known as the 'Little Cyclone' in tribute to her extraordinary courage and tenacity. And she is an inspiration. From nursing wounded Allied servicemen, de Jongh will go on to establish the most famous escape line of the Second World War, saving the lives of more than 800 airmen and soldiers stranded behind enemy lines.

The risks, however, will be enormous. The cost, unspeakably tragic. Her story is shot through with the constant terror of discovery and interception - of late-night knocks at the door, of disastrous moonlit river crossings, Gestapo infiltrators, firing squads and concentration camps. It is also a classic true story of fear overcome by giddying bravery. Estimates of the number of times that de Jongh herself successfully escorted downed airmen across the border into Spain in 1941 and 1942 vary from 16 to 24 round trips. The number of persons, mostly airmen, she escorted successfully is about 118.

Originally published shortly after the war, Little Cyclone is thus a mesmerising tale of the best of humanity in the most unforgiving circumstances: a remarkable and inspiring account to rival the most dramatic of thrillers. Royalties from the sale of this book will go to the Airey Neave Trust. The objective of the trust is to support and promote research that contributes in a practical way to the struggle against international terrorist activity.

De Jongh rejected efforts by the British and the Belgian government in exile to control or direct the Comet Line. British agent Donald Darling (code name "Sunday") who worked for MI6 and MI9 gave her the code name of "Postman", and that's now the title of a second book on de Jongh written by Michael Kenneth Smith (2018). In 1943 she finally got betrayed and arrested herself, and then interrogated nineteen times by the Abwehr (German military intelligence) and twice by the Gestapo. Although she admitted being the leader of the Comet Line to protect her father who was under suspicion, the Germans did not believe that this slight, young woman was more than a minor helper.

Underestimation of de Jongh's importance in the Comet Line probably saved her from execution. Later, while she was a prisoner in Ravensbrück, the Gestapo realized who she was and searched for her, but she eluded them by hiding her identity. After her concentration camp experiences, de Jongh resurfaced in summer 1945 in the middle of the night at Donald Darling's Paris Awards Office. She still wore the pink and white striped dress that was the camp uniform. She was thin and suffering from health problems that lasted for the rest of her life.

Andrée de Jongh was awarded after the war the George Medal (the supreme British civilian decoration), the US Medal of Freedom with golden palms, the Presidential Medal of Freedom (the supreme US civilian decoration), the Belgian Croix de Guerre with palms, and made Chevalier of the French Legion d'honneur and of the Belgian order of King Leopold. She continued her life with a sense of purpose, married fellow resistance member Florentino Iñiguez and moved to the Congo, where she dedicated herself to humanitarian work by working amongst people affected by leprosy. She also worked in Cameroon, Ethiopia and Senegal before ill health brought her back to Belgium. In 1985 she was made a Countess in the Belgian nobility by King Baudouin.

Airey Neave served as an intelligence agent for MI9 in World War Two. This was a section of the British Directorate of Military Intelligence, part of the War Office. During the Second World War it was responsible for obtaining information from enemy prisoners of war. The author of several highly acclaimed books on the Second World War, Neave died in 1979 in an IRA a car-bomb attack at the House of Commons. Margaret Thatcher was due to broadcast to the nation that evening, but cancelled her plans due to her grief at Neave's death.