This page is a permanent link to the reply below and its nested replies. See all post replies »

DDonde · 31-35, M

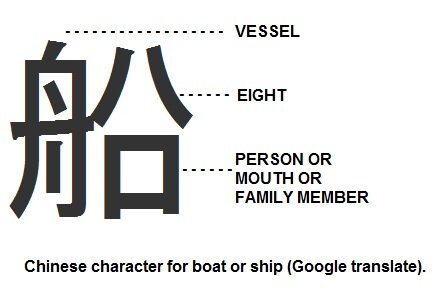

The character should be thought of as

semantic 舟 (“boat”) + phonetic 㕣

semantic 舟 (“boat”) + phonetic 㕣

LoveTriumphsOverHate · 36-40, M

@DDonde Thank you. I've read that possible explanation also. Many scholars familiar with Chinese hieroglyphics have concluded it's just as likely that 㕣 has semantic meaning. Both theories are inconclusive.

DDonde · 31-35, M

@LoveTriumphsOverHate They're not hieroglyphics, they're characters. You know what the semantic meaning of 㕣 is?

LoveTriumphsOverHate · 36-40, M

@DDonde T

Most of the world’s languages are written alphabetically; in an alphabetic writing system the basic components represent sounds only without any reference to meaning. For example, the letter “b” in English represents a voiced bilabial stop, but no particular meaning can be attached to it in its function as a letter of the alphabet. Chinese writing is logographic, that is, every symbol either represents a word or a minimal unit of meaning. When I write the character , it not only has a sound, niu, it has a meaning, “cow.” Only a small number of symbols is necessary in an alphabetic system (generally under 50), but a logographic system, such as Chinese writing requires thousands of symbols.

From the aspects of sound, every Chinese character represents one syllable. Many of these syllables are also words, but we should not think that every word in modern Chinese is monosyllabic. The word for “television,” for example, is , dianshi; since this word has two syllables, it is necessary to write it with two characters. Each of these characters has an independent meaning: dian means “electric,” and shi means “vision”; in this particular case neither of the characters can be used alone in modern Chinese as a word; however, in the Chinese of two and a half millennia ago, both characters were independent words. So, when we say that Chinese has a logographic writing system, one in which each basic symbol represents an independent syllable, we are speaking of the Chinese of a much earlier period.

Most of the world’s languages are written alphabetically; in an alphabetic writing system the basic components represent sounds only without any reference to meaning. For example, the letter “b” in English represents a voiced bilabial stop, but no particular meaning can be attached to it in its function as a letter of the alphabet. Chinese writing is logographic, that is, every symbol either represents a word or a minimal unit of meaning. When I write the character , it not only has a sound, niu, it has a meaning, “cow.” Only a small number of symbols is necessary in an alphabetic system (generally under 50), but a logographic system, such as Chinese writing requires thousands of symbols.

From the aspects of sound, every Chinese character represents one syllable. Many of these syllables are also words, but we should not think that every word in modern Chinese is monosyllabic. The word for “television,” for example, is , dianshi; since this word has two syllables, it is necessary to write it with two characters. Each of these characters has an independent meaning: dian means “electric,” and shi means “vision”; in this particular case neither of the characters can be used alone in modern Chinese as a word; however, in the Chinese of two and a half millennia ago, both characters were independent words. So, when we say that Chinese has a logographic writing system, one in which each basic symbol represents an independent syllable, we are speaking of the Chinese of a much earlier period.

LoveTriumphsOverHate · 36-40, M

@DDonde look up the word Hieroglyph.

Hieroglyph

Definition: a stylized picture of an object representing a word, syllable, or sound, as found in ancient Egyptian and other writing systems

Hieroglyph

Definition: a stylized picture of an object representing a word, syllable, or sound, as found in ancient Egyptian and other writing systems

LoveTriumphsOverHate · 36-40, M

@DDonde

Characteristics

The Chinese traditionally divide the characters into six types (called liu shu, “six scripts”), the most common of which is xingsheng, a type of character that combines a semantic element (called a radical) with a phonetic element intended to remind the reader of the word’s pronunciation. The phonetic element is usually a contracted form of another character with the same pronunciation as that of the word intended. For example, the character for he “river” is composed of the radical shui “water” plus the phonetic ke, the meaning of which (“able”) is irrelevant; the combined shui-ke suggests the word he meaning “river.” Seventy-five percent of all Chinese characters are of this type.

The other types of characters are xiangxing, characters that were originally pictographs (these have a semantic element originally expressed by a picture; for example, the character for tian “field” represents a field by means of a square divided into quarters); zhishi, characters intended to symbolize logical or abstract terms (e.g., er “two” is indicated by two horizontal lines); huiyi, characters formed by a combination of elements thought to be logically associated (e.g., the symbols for “man” and “word” are combined to represent the word meaning “true, sincere, truth”); zhuanzhu, modifications or distortions of characters to form new characters, usually of somewhat related meaning (e.g., the character for shan “mountain” turned on its side means fou “tableland”); and jiajie, characters borrowed from (or sometimes originally mistaken for) others, usually words of different meaning but similar pronunciation (e.g., the character for zu “foot” is used for zu “to be sufficient”).

Chinese script, as mentioned above, is logographic; it differs from phonographic writing systems—whose characters or graphs represent units of sound—in using one character or graph to represent a morpheme. Chinese, like any other language, has thousands of morphemes, and, as one character is used for each morpheme, the writing system has thousands of characters. Two morphemes that sound the same would, in English, have at least some similarity of spelling; in Chinese they are represented by completely different characters. The Chinese words for “parboil” and for “leap” are pronounced identically. Yet there is no similarity in the way they are written.

Characteristics

The Chinese traditionally divide the characters into six types (called liu shu, “six scripts”), the most common of which is xingsheng, a type of character that combines a semantic element (called a radical) with a phonetic element intended to remind the reader of the word’s pronunciation. The phonetic element is usually a contracted form of another character with the same pronunciation as that of the word intended. For example, the character for he “river” is composed of the radical shui “water” plus the phonetic ke, the meaning of which (“able”) is irrelevant; the combined shui-ke suggests the word he meaning “river.” Seventy-five percent of all Chinese characters are of this type.

The other types of characters are xiangxing, characters that were originally pictographs (these have a semantic element originally expressed by a picture; for example, the character for tian “field” represents a field by means of a square divided into quarters); zhishi, characters intended to symbolize logical or abstract terms (e.g., er “two” is indicated by two horizontal lines); huiyi, characters formed by a combination of elements thought to be logically associated (e.g., the symbols for “man” and “word” are combined to represent the word meaning “true, sincere, truth”); zhuanzhu, modifications or distortions of characters to form new characters, usually of somewhat related meaning (e.g., the character for shan “mountain” turned on its side means fou “tableland”); and jiajie, characters borrowed from (or sometimes originally mistaken for) others, usually words of different meaning but similar pronunciation (e.g., the character for zu “foot” is used for zu “to be sufficient”).

Chinese script, as mentioned above, is logographic; it differs from phonographic writing systems—whose characters or graphs represent units of sound—in using one character or graph to represent a morpheme. Chinese, like any other language, has thousands of morphemes, and, as one character is used for each morpheme, the writing system has thousands of characters. Two morphemes that sound the same would, in English, have at least some similarity of spelling; in Chinese they are represented by completely different characters. The Chinese words for “parboil” and for “leap” are pronounced identically. Yet there is no similarity in the way they are written.

LoveTriumphsOverHate · 36-40, M

@DDonde As I stated, neither theory is conclusive. It cannot be clearly established whether the logogram contains phono-semenatic compounds or is meant as ideographic. Yet you insist 㕣 is phonetically imposed. On what evidence do you base this inference on?

DDonde · 31-35, M

@LoveTriumphsOverHate The evidence I base it on is that every resource I have consulted tells me that 㕣 is the phonetic component of 船 and none of them have said that it is a semantic + semantic compound. I searched for a site that says the 㕣 is semantic and I have yet to find one. Meanwhile I have found many that say it's the phonetic component of 船. I would like to see where you are getting your claim that it is the semantic component from.